Who, What, When, Where, How & Why …

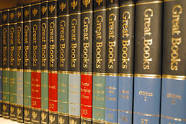

In 1952 Encylcopaedia Britannica published a 54-volume set called Great Books of the Western World, containing what the editors considered to be the most significant works of Western culture. Robert Hutchins, president of the University of Chicago and editor of the series, wrote a lengthy essay entitled The Great Conversation to kick off the project. Hutchins discusses why modern folks should spend time reading the writings of thinkers who have been dead and gone for centuries. His point is that the great minds of the ages have engaged in a dialogue about the big ideas with which mankind has wrestled since the beginning of time. The question is, shall we join in with this conversation?

In 1952 Encylcopaedia Britannica published a 54-volume set called Great Books of the Western World, containing what the editors considered to be the most significant works of Western culture. Robert Hutchins, president of the University of Chicago and editor of the series, wrote a lengthy essay entitled The Great Conversation to kick off the project. Hutchins discusses why modern folks should spend time reading the writings of thinkers who have been dead and gone for centuries. His point is that the great minds of the ages have engaged in a dialogue about the big ideas with which mankind has wrestled since the beginning of time. The question is, shall we join in with this conversation?

At Wilson Hill Academy we chose the term “The Great Conversation” for our Great Books courses, because we want our students to enter into a discussion that has been taking place long before Plato and will continue long after we are gone. Hutchins explains that, “In a conversation that has gone on for twenty-five centuries all dogmas and points of view appear. Here are the great errors as well as the great truths. The reader has to determine which are the errors and which the truths.” As Christians we have considerable help in that task of discerning truth, as we believe the Word of God is the final authority. Whether it’s The Great Gatsby, The Epic of Gilgamesh or The Canterbury Tales, the Bible serves as the final word in all discussions. The challenge is to bring that ultimate truth to bear as we enter into this conversation in a meaningful way. That is the focus of this series of classes at WHA.

The term “The Great Conversation” itself implies that there is an active, open-ended discussion going on. A dialogue of this kind can only take place in a live, real-time environment. It implies that there must be real people present with whom to discuss and debate the big ideas. The student interacts with the writer of a great work, like Plato’s Republic, for example, and then comes to a live class to discuss those ideas with a group of students who have also read the work. But How, you might ask, can we get up to speed on 25 centuries of discussion in a few short class periods?

We’re glad you asked. Since no student can exhaust the entire canon of the great works of Western culture in high school (nor should he try), the point of The Great Conversation is not to read every great work. It is not even necessarily to read every page of the works we do read. The point is not only to enter into a meaningful discussion of the great ideas within this class, but also (and perhaps primarily) to acquire the tools for continuing the discussion for a lifetime. Hutchins explains that the student “cannot expect to store up an education in childhood that will last all his life. What he can do in youth is to acquire the disciplines and habits that will make it possible for him to continue to educate himself all his life.” It’s not a hot dog eating contest. Devouring 69 hot dogs in 10 minutes (the current record if my research is correct) is not a healthy activity. In fact, it may be hazardous to your health! Likewise, cramming too many works into the brain without learning how to process and approach the ideas is not healthy. It’s not how much you eat. It’s what you eat. It’s not the volume that is most important; rather, it’s learning how to engage the ideas, think Christianly, and arrive at godly conclusions.

A valuable tool we use to fill in some of the gaps from works, or portions of works we do not read, is the Discussion Board. Outside of class students are engaged in written discussions and debates in a forum-like environment. Often, students are required not only to respond to a difficult or controversial question, but also to interact with several other student responses on the forum. The Discussion Board allows the student to continue The Great Conversation, and to do so in a way that sharpens writing skills.

The curriculum we use as a general guide is the Omnibus textbook series. Omnibus provides two sets of books lists, a “primary” list consisting of works of history, theology and literature in chronological order, and a “secondary” list made up of books that complement the primary books. These secondary books tend to be works of literature, and do not necessarily move in a chronological order, but in many ways reflect themes of the particular time period.

We have seen these two sets of books taught various ways at different schools, but have concluded that the ideal way to teach them is together in one, unified course. Separating them out, and teaching them as two separate courses misses the point of having the two lists in the first place. The two sets of books are designed to complement each other in ways that make the teaching of the material quite exciting. For example, we teach Genesis alongside C.S. Lewis’s The Magician’s Nephew so students can discuss various views of the Fall and Creation. We teach Herodotus and The Horse and His Boy together so we can define and discuss the implications of multiculturalism. Peter Kreeft’s books don’t make as much sense if you don’t teach them alongside the works of Plato. The list goes on and on, but the point is obvious. When the two lists are taught separately, the two different teachers may not necessarily make those connections, and thus miss those golden opportunities to tie the two together.

There is no doubt that by and large, education today neglects the study of the Great Books. Hutchins was concerned that if we fail to hear the sages of the past, we will not know how to live now. He bemoaned that fact that we tend to “lead lives comparatively rich in material comforts and very poor in moral intellectual and spiritual tone.” He also believed that understanding and discussing the Great Books would give us a “standard by which to judge all other books.” The reasons for reading the Great Books are numerous. At Wilson Hill Academy we want to bring our students into a discussion that has been going on for a very long time, but at the same time, we want to teach them how to continue the conversation in a way that challenges our modern culture with the claims of the gospel of Jesus Christ.

Submitted by Bruce Etter, Head of School (and instructor in The Great Conversation series) at WHA